The recent shuffling of Australia’s cabinet indicates changes in immigration policy, which are in line with past immigration trends and public concerns. Examine the effects and potential ramifications of Australia’s recent reforms to its immigration laws.

The Albanese government just reshuffled its cabinet, which may indicate a change in policy regarding immigration. A possible political response to the mounting immigration concerns is indicated by the removal of Home Affairs Minister Clare O’Neil from her position and the assignment of Andrew Giles, who was previously the minister of immigration, to the Skills and Training portfolio (now part of the outer ministry).Giles’ downgrade seems to be a result of the community receiving the release of illegally detained immigrants, some of whom have criminal convictions, into the open. He left because of public discomfort about the ongoing high levels of immigration. When O’Neil was the Home Affairs minister last year, he promised to dramatically cut Australia’s immigration intake. However, his rhetoric was more ambitious than his actual actions, as he only adjusted the exaggerated figures that were observed after the outbreak.

Their reorganization occurs in spite of recent initiatives to limit the number of foreign students; yet, these measures proved unable to protect Giles and O’Neil from the political ramifications. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese lost a great chance to allay public fears by educating Australians about the historical trends of immigration, rather than placing the burden on his ministers.

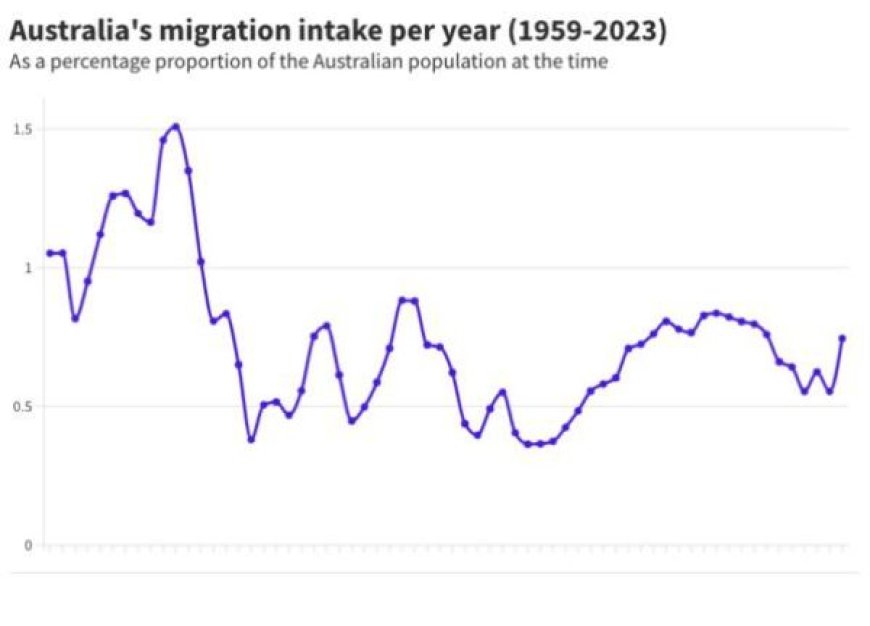

Analyzing historical statistics makes it evident that Australia has previously seen comparable, if not higher, immigration levels. Actually, compared to its peak in the late 1960s, Australia now receives around half as many immigrants as it did at that time, as a percentage of the total population.

An Historical Angle

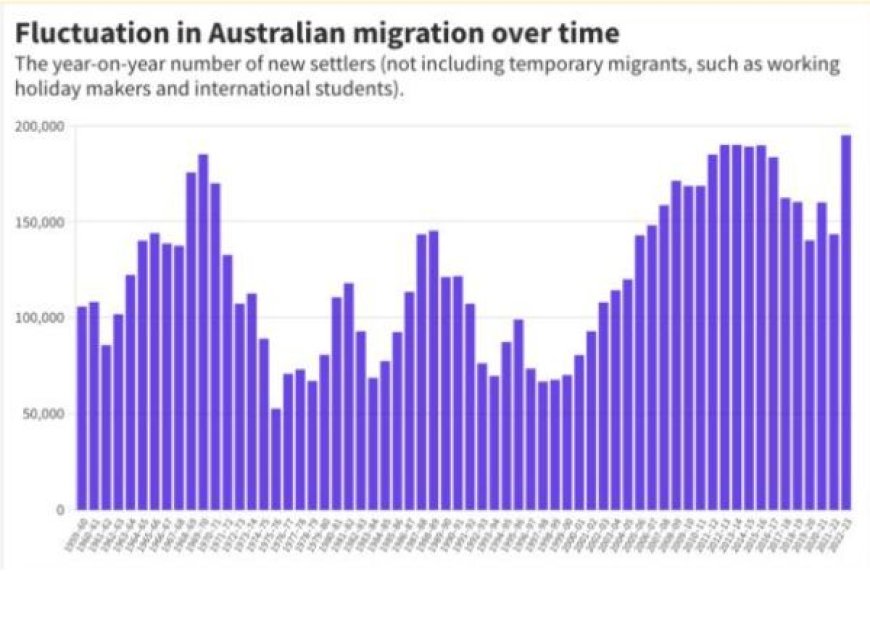

Figure 1 depicts Australia’s permanent migration program and the ebb and flow of migration levels from 1959–1960 to 2022–2023, primarily as a result of the country’s political and economic circumstances. This data does not include temporary migrants who apply for permanent residency or depart at the expiration of their visas, such as working vacationers and international students. It can be deceptive and unnecessarily alarming to include temporary migrants in estimates of Australia’s “net overseas migration” intake—which some media outlets assert surpasses 500,000.

A major immigration program was driven by the post-World War II economic boom and the pressing need to grow the population. This inflow was partly caused by Europeans, especially Britons, receiving subsidies for travel under the “assisted passages” program.

But by the 1970s, the Whitlam Government’s policies and better economic conditions in Europe had eliminated the primary cause of emigration, which had led to a decline in immigration. Gough Whitlam was praised by the political left, yet his views on immigration were nuanced. Due to the economic collapse that followed the 1973 oil crisis and long-standing Labor anxieties that immigrants would replace native-born workers in the workforce, his administration not only officially abolished the White Australia policy but also decreased immigration to its lowest level since World War II.

Fluctuations in Immigration

Immigration surged during the Fraser Administration (1975–1983), especially to handle the flood of around 60,000 Vietnamese refugees following the Vietnam War. This, however, was not to last, as during the recession of the early 1980s, numbers began to decline once more. Later, the Hawke/Keating administrations opened up Australia’s economy to the outside world, which resulted in a dramatic increase in immigration in the 1980s. However, the recession of the early 1990s dampened this boom.

Despite initially restricting immigration in response to growing anti-immigration sentiment, particularly from Pauline Hanson, the Howard Government finally oversaw a major expansion of the program. Only briefly did the Global Financial Crisis of 2007–2009 impede this rise.

Under the governments of Tony Abbott, Kevin Rudd, and Julia Gillard, the immigration program kept growing, proving the strength of the Australian economy. But even before the COVID-19 outbreak, immigration started to fall, in part because Home Affairs Minister Peter Dutton (2017–21) increased the screening of visa applications in an effort to weed out false claims.

The true cause of the fall in immigration was a higher-than-usual rejection rate, especially for older applicants with complex health histories who were judged too “high risk” for admittance, despite assertions that these cuts were intended to relieve urban congestion.

This late 2010s example demonstrates how immigration is frequently utilized as a political wedge to solve socioeconomic concerns that are unrelated to immigration, such poor urban planning.

An Extended Perspective

The raw number of new immigrants as a percentage of Australia’s total population is displayed in Figure 2. Australia’s population is expected to increase from 10 million in 1959 to 26 million in 2023, with a declining general trendline. When immigration peaked in the late 1960s, 1.5% of Australia’s population was foreign-born. This percentage has never surpassed 0.84% since that time.

These numbers imply that worries about immigration taking over are baseless. Current immigration levels are well within historical norms when compared to the past 50 years, especially in light of Australia’s population increase.

The greater reliance on temporary immigration by Australia, which includes overseas students, working vacationers, and New Zealanders who are free from visa rules, is new. Reducing immigration would be detrimental to Australia’s economy and society, whether it were temporary or permanent.

The temptation for politicians to use immigration as a band-aid solution to domestic issues may be strong, but there may be long-term, serious consequences for Australia’s economy, society, and standing abroad.